A WHO report shows that 35% of women, worldwide, have experienced violence, and 39% of women were murdered at the hands of their partner. These figures are frightening, and as a woman who has experienced this type of violence, I know how easily it can happen. However, what I want to explore here is the role that technology, specifically connected systems termed under the banner of the “Internet of Things (IoT)” have on domestic violence and abuse?

Before I begin, we need to look at what the word ‘violence’ means. Firstly, violence can be both physical and non-physical. It is an aggressive act, performed using methods that can be psychological, sexual, emotional or economic. I gave figures above showing violence against women, but of course, men experience violence too – including domestic. However, technology may add a particular slant to violent and controlling acts – offering a reach to the abuser that they may otherwise not have.

The IoT Mantra Should Be Do No Harm

What if you had a one-night stand? While at your place you let this person use your Wi-Fi. You have, quite rightly, password protected your network. So, you hand over your password which gives them global access to your home network. They get up at 6 am and walk out the door, still holding your password. You forget to change it, easily done. What’s the worst that can happen? Well, if this person turns out to be malicious and wants to hurt you, they can potentially use this access to perform a Man-in-the-Middle attack, stealing your personal data; insert malware; download porno images via your IP address. They could also potentially hijack your IoT devices. All that is needed is a readily available Wi-Fi Pineapple and an unsecured IoT device.

This does not have to be the case, of course, but it comes down to design, education, and the policy makers – more on this later.

According to research by Metova, around 90 percent of U.S. consumers now have a smart home device. But who is controlling those devices?

Researcher and Lecturer at University College London (UCL) Dr Leonie Tanczer, has, along with her team members Dr Simon Parkin, Dr Trupti Patel, Professor George Danezis and Isabel Lopez, looked at how the IoT can, and will likely, contribute to gender-based domestic violence. Their interdisciplinary project is named “Gender and IoT” (#GIoT) and part of the PETRAS IoT Research Hub.

I spoke with Leonie, who has extensive knowledge in this area. She pointed me to some of their GIoT resources, including a tech abuse guide, a dedicated resource list for support services and survivors, as well as a new report that features some of the research groups pressing findings.

Leonie also shared some relevant insights, some of which I would like to highlight below.

Is the IoT an issue for domestic violence now?

Leonie and her team have been working for the past year at how Internet-enabled devices could be used as a controlling mechanism within a domestic abuse context. The team has, so far, concluded that the threat is imminent but not yet fully expressed. As of now, Spyware, and other features on laptops and phones are primarily being featured in tech abuse cases. However, with the expected expansion of IoT systems as well as their often intrusive data collection and sharing features, IoT-facilitated abuse cases are a question of when, not if.

What unique issues exist between IoT and domestic violence?

One may try to regulate the security of an IoT device by putting some of the best and most robust protection measures in place. However, in a domestic abuse situation, coercion can override any of these processes. If one partner is responsible for their purchase and maintenance, and has full control as well as knowledge over their functionalities, the power imbalance can result in one person being able to monitor and restrain the other. The team’s policy leaflet emphasises this dynamic quite vividly.

Can you map the IoT device use pattern with an abusive relationship?

When it comes to the safety and security of a victim and survivor – in particular, in regards to tech – we have to consider the three phases of abuse. These phases interplay with the security practices a person has to adopt.

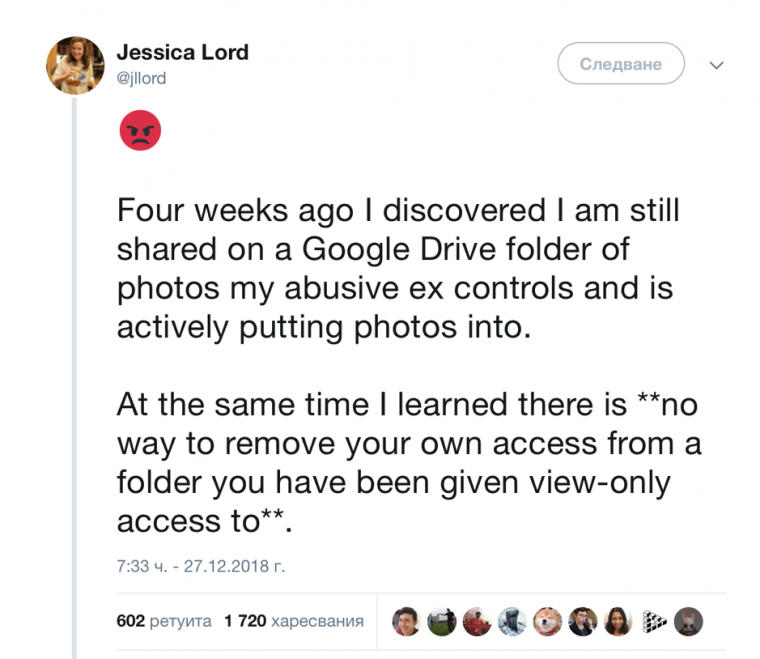

For instance, while still in a co-habiting situation, the abusive partner may use devices in the home to spy on the other. Their online usage can be monitored, conversations recorded or filmed. Once a woman has extracted herself from this situation, they may seek help at a local shelter. In this instance, many are advised to simply stop using technology to prevent a perpetrator from contacting or locating them. However, the third phase in which a person has to effectively “reset” their life is equally as central, but becomes extremely hard in our interdependent society. During this period, women will have to change their passwords, regain control over their accounts, and try their best to identify any devices and platforms – including IoT systems – that they may have shared with the perpetrator. – This can become really tricky and I don’t think that we have properly thought about how to ease this process for them.

When Good IoT Devices Become Bad

Leonie also stressed in our conversation that industry stakeholders must take heed of the research being performed in this area and consider how their system might lend itself to forms of abuse. In the identity space, which I work in, there is a saying, “The Internet was designed without an identity layer”. This has led to a kind of retro-fix for the Internet to try and overlay identity – it is complicated and messy and has yet to be fully fixed; retro-active fixing of missing functionality is not the best way to design anything.

I agree with Leonie, we need to ensure that the IoT is designed to guarantee that misuse is minimized at the technology level. However, Leonie also points out that social problems will not be solved by technical means alone. Besides, statutory service such as law enforcement, policymakers, as well as educational establishments, and women’s organisation and refuges need to be incorporated into the design of these systems and made aware of this luring risk. Proactivity is therefore needed and will help to ensure that we don’t repeat technical mistakes we have done in the past.

Some Anti-Abuse Advise on Design and the IoT

During our discussion, Leonie gave me some ideas about design issues her team has found during lab sessions testing IoT devices. These include:

1.Remove any unintentional bias in the service – this can be helped by including multidiscipline people, from diverse backgrounds, on design teams

2.Enable relevant prompts – send out alerts on who has connected to what? The GIoT team suggest that prompts could be used to inform users about essential details, including what devices are or try to connect to their IoT systems or what devices track their location.

3.Offer more transparency and support – offer clear and unambiguous manuals, prepare policies on what helpline staff can do to advice victims should they inquire about guidance, and allow to switch off and on features that user’s need.

Overall, technology-enabled abuse is a human-centric issue and technology alone cannot fix it. We need to work towards a socio-technical solution to the problem.

Conclusion

IoT devices are becoming an extension of our daily lives. Unfortunately, it is inevitable they will become weaponized by people who wish to do us harm – and this will include abuse within a domestic context.

Design is a crucial first step in helping to minimize the use of Internet-enabled devices as weapons of control. Privacy issues, like the recent Apple iPhone Facetime bug, demonstrate this well. The bug was a design flaw. It allowed, under certain circumstances, a caller to listen to people in the vicinity of the phone without the call being picked up. It has been downplayed because those circumstances were not common. However, the does not negate the point that testing the design of user interfaces and the UX needs to be holistic and place privacy as a key requisite to sign off a UX.

Designing IoT devices should to be done by a multi-disciplinary team. We must remove unintentional bias and use different viewpoints and experiences. Only by combining the social with the technological can we hope to ensure that our technology is not misused for nefarious reasons.

Thank you to Dr. Leonie Tanczer for help in creating and editing this article.

Originally posted on www.iotforall.com.

Author

Susan Morrow

Susan Morrow

Having worked in cybersecurity, identity, and data privacy for around 35 years, Susan has seen technology come and go; but one thing is constant – human behaviour. She works to bring technology and humans together.

Find her @avocoidentity